This post is a reprint of an article written by James Finn of the Mississippi Center for Investigative Journalism.

With workers sick and workforces depleted, two Mississippi poultry plants have permission to ratchet up processing line speeds to increase production during the pandemic — at the risk, union leaders say, of worker safety in one of the country’s most dangerous industries.

Union leader Randy Hadley, who represents 3,000 Mississippi poultry workers, said COVID-19 has slowed job applications during the summer months and forced existing workers to quarantine, and said the workforce he represents was seeing absenteeism as high as 26% in late July.

“People are scared of coming into the facility to apply for a job because of the cases that are in the facility,” Hadley said.

In the early days of Mississippi's battle against the coronavirus, its thousands of poultry workers toiled unprotected on the frontlines. In the fifth-largest producing state in the nation, poultry workers named essential workers by the Trump administration arrived for shifts at plants that for weeks offered few safety measures against the virus — working the chicken-processing lines without masks or distance.

Now, workers and advocates say plants are making hand sanitizer, gloves and masks available. But COVID-19 continues to plague the plants’ workforce as Mississippi case numbers remain high. As of August 6, the Mississippi Department of Health (MDH) had identified 27 COVID-19 outbreaks in meatpacking facilities across the state. At least 18 chicken-processing facilities had outbreaks.

Hadley is president of the mid-South council of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, and represents workers at Tyson Foods plants in Carthage and Forest and DG Foods’ plant in Hazlehurst. He said he knew of 72 workers at the two Tyson plants sick with COVID-19 as of July 10, and that another 72 workers at the two facilities were in quarantine.

Tyson’s Forest plant and Wayne Farms in Laurel were among 15 poultry plants across the South granted waivers by the USDA in April that allowed them to increase processing line speeds, according to a report by the National Employment Law Project. The waivers allowed the plants’ lines to process up to 175 birds per minute, up from the usual 140.

The 15 plants received waivers despite histories of severe injuries, Occupational Safety and Health Administration violations or recent COVID-19 outbreaks, according to the report.

Besides COVID-19 cases Hadley described at Tyson’s plant in Forest, that plant also had a “severe injury” complaint from 2016, according to OSHA data. A Tyson employee in March of that year amputated a finger with a saw while cutting into a chicken on the processing line. At Wayne Farms, a worker in August of 2016 amputated a middle fingertip while removing a twisted belt from a motor.

Hadley said line speeds pose risk in the two plants he represents that didn’t get waivers, too, because they have continued to run lines at “normal” speeds — 140 birds per minute — even as workers are out sick.

“If you continue to run your lines at the same speed, and you have nearly 30% of your people missing work, you can only imagine the stress and the strain that's put on the body to try and keep up,” he said.

Stuart Appelbaum, president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union and vice president of the United Food and Commercial Workers’ Union, which represents workers at Koch and Peco Foods’ Mississippi plants, called waiving line-speed limits during the pandemic “obscene.”

“The meat industry and the poultry industry have used the pandemic as an excuse to do things that they've always wanted to do anyway, because they have the mistaken belief that increasing line speeds leads to increasing profit,” Appelbaum said. “That’s counter-productive, because as more people become sick because of poultry companies' policy, they're going to produce less, not more.”

On July 9, Mississippi 2nd District U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, a Democrat, helped introduce the Safe Line Speeds in COVID-19 Act, which would suspend those waivers. The act would place stricter rules on an industry that has gone largely unregulated during the pandemic in part because of a hands-off approach from OSHA, the federal agency tasked with regulating poultry plants, which faces a lawsuit from meatpacking workers in Pennsylvania. It has been referred to the House committees on Agriculture, Education, Labor, and Energy and Commerce.

Less than three weeks later, the United Food and Commercial Workers’ Union sued the USDA over the line speed waivers, alleging the waivers violated the Administrative Procedures Act by not providing a public comment period.

Hard-working people doing the work that very few in the community will do’

Last November, Thompson, who chairs the House Committee on Homeland Security, presided over a hearing at Tougaloo College on the ICE raids that three months prior swept across Mississippi Poultry plants and led to the arrest of 680 poultry workers. The raids “just devastated those communities,” Thompson told the MCIR. adding that Mississippi’s immigrant laborers are “not drug pushers or members of MS-13, they’re hard-working people doing the work that very few in the community will do.”

The pandemic is not the first time that meatpacking plants have been given permission to raise line speeds. The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service announced in January 2019 that it would allow some poultry processing plants to increase line speed from 140 birds per minute to 175 birds per minute through a waiver program. The announcement marked a change of direction from January 2018, when the USDA and FSIS retracted a proposed rule to remove any line speed restrictions at poultry plants.

Black and Latino workers, who are also among the most vulnerable to COVID-19, make up the majority of Mississippi chicken plants’ labor force. According to a study by the Center for Economic and Policy research, about half of meatpacking workers in the U.S. live in low-income households and one in seven do not have health care.

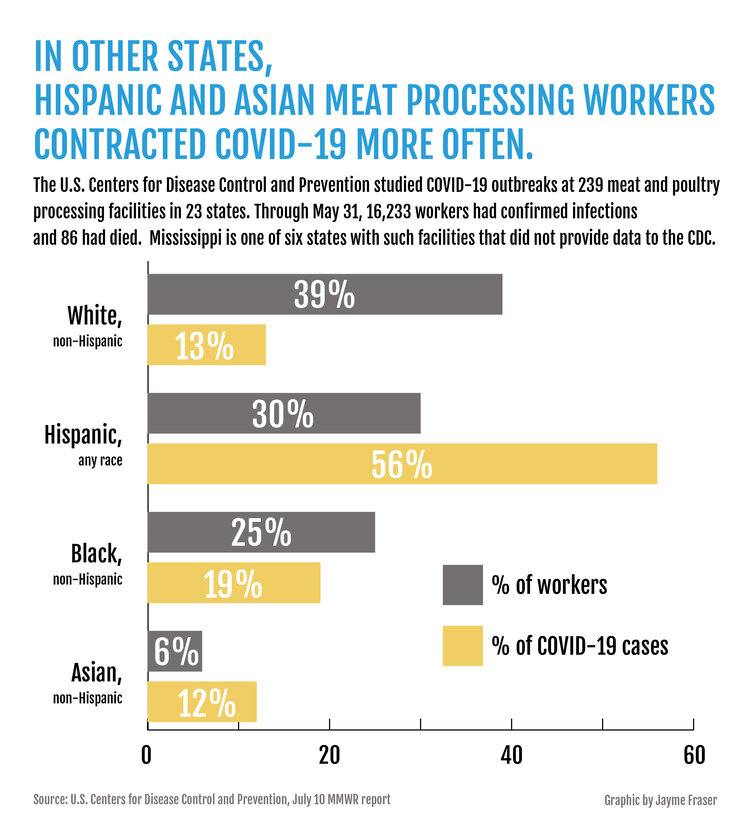

A CDC analysis of coronavirus outbreaks at meat processing plants found that while Hispanic people made up 30% of the workforce studied, they accounted for 56% of COVID-19 cases. Asians -- including Pacific Islanders who also are employed at high rates in poultry plants -- accounted for 6% of the workforce and 12% of the cases. Mississippi is one of six states that did not contribute data for the federal analysis.

Separately, a CDC team studied outbreaks in northwest Arkansas at the request of state officials. The group of scientists concluded in July that cases spiked because the state had failed to prioritize testing in high-risk environments like meatpacking plants and in multigenerational households, where many Latino and Marshallese workers lived. The review also noted that the two counties with the state’s largest population of Spanish-speaking residents had just one caseworker who spoke that language to do contact tracing.

Tyson Foods’ Carthage and Forest plants are located in Scott and Leake counties, two of the most socially vulnerable counties in Mississippi, according to the CDC’s social vulnerability index. Those counties also have two of the highest per-capita COVID-19 case rates in the state. Those counties also have a larger proportion of Latino residents than the state as a whole.

Tyson Foods’ Carthage and Forest plants are located in Scott and Leake counties, two of the most socially vulnerable counties in Mississippi, according to the CDC’s social vulnerability index. Those counties also have two of the highest per-capita COVID-19 case rates in the state. Those counties also have a larger proportion of Latino residents than the state as a whole.

Poultry workers the MCIR spoke with said they feel safer now that plants are providing personal protective equipment, but that going to work still presents risks to health and safety. Many had contracted the virus.

John, a worker at the Tyson plant in Carthage who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution, caught COVID-19 working in the plant in April, but has since recovered. “At the beginning, there was nothing — no masks, no soap, no sanitizer, nothing,” he said in an interview translated from Spanish. “Workers would come to work like it was normal. Now that’s changed.”

But even with such safety available, he said social distancing is challenging in the plant where employees often stand shoulder-to-shoulder on the processing lines.

“People work in close quarters, but they try to take precautions,” John said.

Tyson Foods has tested workers in its plants around the country for the virus and released testing results for some plants, but has yet to do so for plants in Mississippi. In an email, a Tyson spokesperson directed the MCIR to a press release outlining the company’s new “COVID Monitoring Strategy.”

The company has already “tested nearly a third of its workforce,” according to the July 30 release, and plans to test “thousands more workers” across its hundreds of meatpacking plants nationwide in the coming weeks.

However, Hadley said testing has not been mandatory, and employees said some fellow workers have been afraid to get tested because they fear they’ll lose their paychecks.

“If you only have one person working in your family, workers don’t have the money to risk losing two or three weeks’ pay,” said Fredy Salvador, a plant employee who has worked at several Mississippi poultry plants in past years.

Coronavirus another devastating challenge to the community’s efforts to recover

from the trauma of the ICE raids

Hadley said that Tyson workers have had access to sick pay during quarantine periods. But despite being classified as “essential” by Trump’s executive order, workers are not always paid like it. Hazard pay was not initially added to workers’ hourly wage at the plants he represents, Hadley said.

“The plants wouldn't put nothin' on the hour, unless it was tied to attendance, which encouraged people to come to work sick,” Hadley said.

Immigrant workers, who are primarily Latino in Mississippi, face additional legal challenges that discourage them from seeking testing or care. This spring, new federal rules took effect that limit who can access certain public benefit programs without forfeiting the ability to seek citizenship. Although coronavirus testing has been excluded, fear remains for many non-citizen workers.

Non-citizens already have reduced access to health care: almost half are uninsured in Mississippi compared to just 12% of citizens. Because federal rules for some benefit programs consider the legal status of all residents in the home, even naturalized citizens access the public safety net less often, leading to 20% being uninsured in Mississippi. Those rates also can be linked to the fact that many immigrant workers take jobs that do not offer benefits such as health insurance or paid time off.

For the Latino community in Forest, where organizer Monica Soto says as many as 140 families had a member detained in the ICE raids a year ago, the coronavirus has added another devastating challenge to the community’s ongoing efforts to recover from the trauma of that day.

Soto is an outreach worker for El Pueblo, an immigration advocacy organization whose Forest office opened last fall in response to the needs created by the raids. The organization has helped pay rent and provide food for workers and their families who have fallen ill, and provides legal representation to those facing court dates after the raids.

Fredy Salvador, a worker at Koch Foods, contracted COVID-19 at work in May, and had to quarantine for 15 days, facing the virus alone after his wife and 3-year-old daughter were deported to Guatemala last year. Sarah Warnock/MCIR

Fredy Salvador, a worker at Koch Foods, contracted COVID-19 at work in May, and had to quarantine for 15 days, facing the virus alone after his wife and 3-year-old daughter were deported to Guatemala last year.

Sarah Warnock/MCIR

“When the raids happened, we needed a lot of community outreach helping with bills, rent and food,” she said. “Then when the virus hit we had clients that had court dates, and that all came to a halt. We had to stop a lot of work. When people started becoming positive with the virus, it was hard to get food or supplies to our families, and even to know who needed what.”

Testing for coronavirus is not just about tracking the disease. It also helps identify people who qualify for support programs. If a person who tests positive can't safely isolate away from others in the home, they can be connected with programs to isolate safely, such as in a hotel room. Without adequate testing, local officials don't know who needs that kind of help. And without targeted outreach campaigns to assuage fears in the Latino community, people will avoid be tested and go without the kinds of support helping other families weather the financial harms of the disease.

In the early days of the virus El Pueblo’s women’s group, Mujeres Unidas, which provides counseling to women who have suffered domestic violence, saw that workers and their families weren’t receiving enough in the way of PPE. So they sewed 1,800 masks — several hundred of which went directly to workers on the plants’ floors.

“We were trying to give them some protection,” Soto said. “They weren't given that.”

Many undocumented workers detained in the raids were left without income, as they had to stop working while reporting for immigration hearings. Maria, who was detained while working at a plant in Morton and now wears an ankle monitor, is one of those workers (the MCIR is referring to her by her first name to protect her identity). Her husband, a construction worker, got sick in June, leaving the couple unable to work.

“If the raids and the virus hadn't happened, my husband and I would have been able to work and we would have been able to take care of our kids,” Maria said. “Now, that’s become extremely difficult. I have three kids. I don't know where I'm going to go. This is the question we face.”

Salvador said he contracted COVID-19 at work in May, and had to quarantine for 15 days, facing the virus alone after his wife and 3-year-old daughter were deported to Guatemala last year.

“Now I’m alone, and it’s not the same if you get sick without anyone to care for you,” he said.

9 comments:

Getting so tired of this cold. High Survivability rate. Even higher panic rate.

@10:03

The illegals that work these plants often have poor health, numerous parasites from the use of human fertilizer in their native gardens, and practice communal living. They are extremely susceptible and are essentially super spreaders. Their US Citizen children are also returning to school.

Great article on behalf of the unions. I'm sure it is a completely accurate representation of all the situations in these plants, working conditions, and the health and safety issues.

I've never known a union organizer, business agent, or the union's PR machine to misrepresent anything; always just like Jack Webb - just the facts.

Should have read the CL yesterday to see the other side of this story with their banner headline - I'm sure it would have given a good investigative reporters view of this 'story.

Yeah, sure. Glad I didn't waste my time with that yesterday, got the same drivel here this morning.

Good bad news find, KF. Keep on digging.

A Disciple speaks.

https://www.wlbt.com/2020/08/24/dr-birx-if-its-safe-go-into-starbucks-mississippi-its-safe-wait-line-polls/

All I see, above, is a bunch of boring, two sentence fucking paragraphs. Who will read through that shit? These people live, travel and work in Covid Factories. And the health department knows it!

Not to worry, those Tyson Crispy Chicken strips will be safe . . . as long as one cooks them "well done" .

Same with PECO chicken from Canton.

Illegals what illegals all these people either have work visas or are U.S. citizens.

9:52 - Can't tell if you're serious or not. Are you with Catholic Charities?

Post a Comment